June 16, 2025 Court of Appeal - Judgments

Claim No: CA 016/2024

THE DUBAI INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL CENTRE COURTS

In the name of His Highness Sheikh Mohammad Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Ruler of Dubai

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL

BEFORE H.E. DEPUTY CHIEF JUSTICE ALI AL MADHANI, H.E. JUSTICE ROBERT FRENCH AND H.E. JUSTICE MICHAEL BLACK KC

BETWEEN

(1) KOREK TELECOM COMPANY LLC

First Claimant/Appellant

(2) KOREK INTERNATIONAL (MANAGEMENT) LIMITED

Second Claimant

(3) SIRWAN SABER MUSTAFA

Third Claimant/Appellant

and

(1) IRAQ TELECOM LIMITED

FOR ITSELF AND IN THE NAME AND ON BEHALF OF INTERNATIONAL

HOLDINGS LIMITED

(2) INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED

Defendants/Respondents

| Hearing : | 1 May 2025 |

|---|---|

| Counsel : | Ms Zoe O’Sullivan KC for the First and Third Claimants/Appellants Mr Tom Montagu-Smith KC and Ms Miriam Schmelzer for the Defendants/Respondents |

| Submissions | Appellants’ Skeleton Argument dated 19 September 2024. Appellants’ Supplementary Skeleton Argument dated 24 March 2025 Respondents’ Skeleton Argument dated 18 December 2024 Respondents’ Supplementary Skeleton Argument dated 23 April 2025 |

| Judgment | 16 June 2025 |

JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEAL

UPON the issue of the final award in ICC Case No. 25194/AYZ/ELU dated 20 March 2023 (the “Award”)

AND UPON the Order of H.E. Justice Shamlan Al Sawalehi dated 14 April 2023 recognising the Final Award issued in case number ARB-009-2023

AND UPON the Claimants’ set aside application dated 20 June 2023 (the “Set Aside Application”)

AND UPON the Order of H.E. Justice Shamlan Al Sawalehi dated 29 August 2024 dismissing the Set Aside Application (the “Order”)

AND UPON the First and Third Claimant’s application seeking permission to appeal the Order (the “PTA Application”)

AND UPON the Order of H.E. Justice Shamlan Al Sawalehi dated 27 November 2024 granting the PTA Application on all grounds

AND UPON hearing counsel for the Appellants and counsel for the Respondents at the Appeal Hearing before H.E. Deputy Chief Justice Ali Al Madhani, H.E. Justice Robert French and H.E. Justice Michael Black KC on 1 May 2025

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED THAT:

1. The Appeal is dismissed.

2. The Appellants will pay the Respondents’ costs of the Appeal to be assessed by the Registrar if not able to be agreed.

Issued by

Delvin Sumo

Assistant Registrar

Date of Issue: 16 June 2025

At: 9am

SCHEDULE OF REASONS

Introduction

1. In an arbitration, which is the subject of this Appeal, the Respondents to the Appeal raised a tortious conspiracy claim against the Appellants. They alleged that the Appellants had corruptly procured a decision of the Communications and Media Commission of the Republic of Iraq (“CMC”) adverse to the Respondents and had caused them to suffer loss and damage. The Tribunal found the claim made out. The Appellants contend that the Tribunal was precluded from making such a finding because it involved canvassing the decision of a foreign state authority contrary to the act of state doctrine and to the public policy of the UAE. The Appeal raises the question of the existence, scope and application of the act of state doctrine in the DIFC and its interaction with the public policy of the UAE.

2. An ancillary question involved the tender to the Tribunal of investigative materials allegedly unlawfully obtained.

The Parties

3. The Appellants are Korek Telecom Company LLC (“Korek”), a company incorporated under the laws of Iraq and Sirwan Saber Mustafa, who resides in Iraq. They were the respondents in the Arbitration, along with Korek International (Management) Ltd (“KI”), a company incorporated under the laws of the Cayman Islands. The Respondents to the Appeal are Iraq Telecom Ltd (“IT”) and International Holdings Ltd (“IH”). They were the claimants in the Arbitration.

Procedural history

4. On 20 March 2023, an ICC Arbitral Tribunal (the “Tribunal”) issued a Final Award (the “Final Award”)1 in the Arbitration. The seat and place of the Arbitration was the Dubai International Financial Centre (‘DIFC”). The claims were brought pursuant to a Shareholders’ Agreement of 10 March 2011 (“SHA”), an Amended and Restated Subscription Agreement dated 27 July 2011 (“Subscription Agreement”) and a Letter Agreement entered into on or around 27 July 2011. The Tribunal made a number of orders in favour of the Respondents to the Appeal, including awards of damages, interest, declaratory relief, specific performance, the costs of the Arbitration and legal costs.

5. A Recognition and Enforcement Order was made on 14 April 2023 in the DIFC Court of First Instance (“DIFC CFI”) in case number ARB-009-2023. On 24 May 2023, the Appellants issued an Application to Set Aside the Recognition and Enforcement Order. On 12 May 2023, H.E. Justice Sir Jeremy Cooke granted a Worldwide Freezing Order against the Appellant, Mr Mustafa in respect of the entirety of the sums due under the Final Award and granted the Respondents permission to enforce the Recognition and Enforcement Order and the underlying Final Award.

6. On 20 June 2023, the Appellants filed an Application to Set Aside the Award. The Application was heard by His Excellency Justice Shamlan Al Sawalehi on 19 February 2024. On 29 August 2024, His Excellency ordered that the Set Aside Application be rejected. The Recognition and Enforcement Order and a Worldwide Freezing Order issued by Justice Sir Jeremy Cooke on 12 May 2023 in claim number ARB-009-2023 were upheld.2

7. On 19 September 2024, the Appellants filed an Appeal Notice seeking permission to appeal His Excellency’s Order. On 27 November 2024, His Excellency ordered that the Permission to Appeal Application be granted on all grounds and the matter be referred to the Court of Appeal for determination.

The Arbitration provisions of the relevant agreements

The Shareholders’ Agreement

8. Clause 47 of the SHA provided for the governing law under the Agreement as follows:

“47. Governing Law

This Agreement, including any non contractual obligations arising out of or in connection with this Agreement, shall be governed by and construed in accordance with English law.”

Clauses 48.1 and 48.2 provided for non-adversarial dispute resolution mechanisms under the Agreement, in circumstances in which:

“… any dispute, controversy or claim of whatever nature arises under, out of, or in connection with this Agreement, including any question regarding its existence, validity or termination or any non contractual obligations arising out of or in connection with this Agreement (a Dispute) …”

9. Clause 48.3 provided for arbitration of disputes not resolved under clauses 48.1 and 48.2:

“48.3 If the parties fail to resolve the Dispute in accordance with clauses 48.1 and 48.2, such Dispute shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration Rules of the ICC (Rules), which Rules are deemed to be incorporated by reference into this clause. The number of arbitrators shall be three (3).”

10. Clause 48.6 provided:

“… The seat, or legal place, of arbitration shall be Dubai International Financial Centre. The language to be used in the arbitration shall be English.”

Subscription Agreement

11. The Subscription Agreement contained similar provisions in clauses 33 and 34.

12. It does not appear from the terms of clause 47 of the SHA and clause 33 of the Subscription Agreement that English law was to apply to the arbitral process. The application of the act of state doctrine for which the Appellants contended depended upon its application as a matter of DIFC Law.

Factual Background

13. The factual history was set out in the Final Award. That history is outlined in the paragraphs that follow.

14. Korek was established by Mr Mustafa and two partners in 2000 in the Erbil Province of Iraq to provide mobile telephone services initially in that region and later across Iraq.3

15. In 2007, the CMC issued a national license to Korek. The CMC is the official body responsible for the regulation of media and telecommunication interests in Iraq.

16. Under the terms of the license Korek was to pay the CMC a license fee of USD 1.25 billion. A first instalment of USD 375 million was paid in or around August 2007. A further instalment of USD 250 million was due on 11 September 2007. Korek approached Agility Public Warehousing K.S.C.P. (“Agility”) for financing to make the payment. The funds were advanced to Korek on 11 September 2007 by a subsidiary of Agility, Alcazar Capital Partners.4

17. Korek required further financial and technical support in 2010. Agility then partnered with Orange S.A., formerly France Telecom S.A. (“Orange”) to provide the funds and expertise required. This involved Orange and Agility acquiring an interest in Korek. The license required CMC’s approval for any direct or indirect change in the control of 10% or more of the issued shares of Korek or total voting rights in Korek. Korek applied to the CMC for its consent to the proposed transaction with Agility and Orange. The consent was granted subject to conditions on 29 May 2011.5

18. Orange and Agility established IT to hold their interest. IH was established as a new holding company. Korek issued all of its existing and newly capitalised shares to IH in July 2011. Mr Mustafa and his fellow investors and another acquired 56% of IH shares, held through KI. IT acquired 44% of IH shares. IT had a Call Option to acquire a further 7% shareholding in IH, which would have given it majority control.6

19. Orange and Agility’s total investment was USD 810 million. The investment was governed by two principal agreements, the SHA and the Subscription Agreement. The parties to the SHA were Korek, Mr Mustafa, KI and IT. The Subscription Agreement was made between IH, Korek, Mr Mustafa and his two partners. At the same time, IT entered into a Shareholder Loan Agreement with IH under which it advanced to IH the sum of USD 285 million. Clause 23 of the SHA contained a Call Option, exercisable by IT giving it the right to call for the transfer of 7% of the fully paid shares in IH sufficient to give it 51% of those shares (“Call Option”). 7

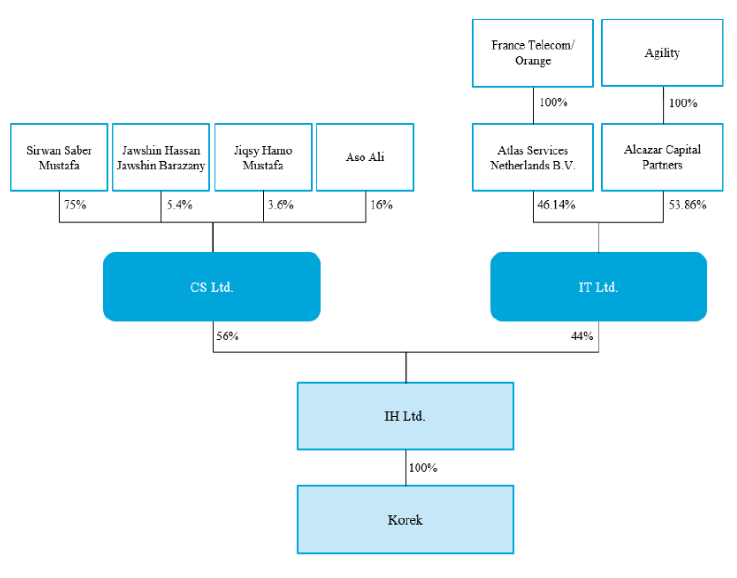

20. The relevant shareholding structures were as follows:

21. Korek was managed by Mr Mustafa as a statutory manager and not by a board of directors. A Korek Supervisory Committee (“KSC”) was established to provide, pursuant to clause 7.1 of the SHA “the overall direction and management of Korek.” It mirrored the composition of the IH board of directors, comprising three directors nominated by KI, three directors nominated by IT and an independent director also nominated by KI. 8

22. On 31 October 2011, the Federal Supreme Court of Iraq accelerated the payment of the fourth instalment of Korek’s license fee in the amount of USD 110 million so that it was due on 18 November 2011 and not in April 2012 as previously advised. Korek then had only USD 15 million at its disposal and would have to raise USD 150 million through loans or capital injections. 9

23. Mr Mustafa advised Korek’s Financing Proposal Committee (“FPC”) on 21 November 2011 that he had obtained a commitment from the IBL Bank (“IBL”) in Lebanon to cover Korek’s payment obligations to the CMC. IT’s representatives were concerned about the duration of the loan and various of its terms. In the event, it was accepted that the IT Shareholder Loan should be subordinated to the IBL Loan pursuant to a separate agreement.10

24. On 10 December 2013, the CMC wrote to Korek alleging that Korek, Agility and Orange had failed to fulfil conditions on which the CMC had approved the 2011 transaction.11

25. The CMC gave Korek one week to provide it with reasons that prevented fulfilment of the conditions and warned that “in light thereof, the actions necessary to protect the telecommunications sector in Iraq shall be taken.” The letter from CMC was signed by Dr Safa Rabih, who was then its Deputy General Director.12

26. On 22 December 2013, Mr Charaf of Korek reported to the KSC that he had been advised by management that Korek was not in a position to reply to the CMC letter as it was not privy to the negotiations that led to the condition or acceptance by the CMC of the Korek transaction, including the partnership with FT-Orange. Nor was management aware of the contents of the SHA. Korek does not appear to have sent any response to the CMC. A final notice was sent by the CMC to Korek in January 2014 requiring a response within a week. A response was provided on 22 January 2014 albeit it was said by IT, from the date stamp on the original, that it was not submitted until after the deadline imposed by the CMC. 13

27. On 29 May 2014, Orange issued a statement to the effect that it was anticipating obtaining majority control of Korek. 14

28. On 10 June 2014, the CMC wrote a letter to Korek stating, in error, that “final benefit from your company does not belong to Iraqi partners who own a stake of over 51% of your company’s capital …, your company’s management has been assigned to the foreign partner, which cannot … be considered anything other than a controlling or major shareholder.” It asserted that Korek must pay a regulatory fee of 18% of its revenues as well as a differential in the regulatory fee. The letter was signed by Dr Rabee as “Chairman of the Executive Body”. 15

29. On 2 July 2014, the CMC issued a “Decision to revoke partnership between Korek Ltd and France Telecom / Agility”. Its decision stated:

“We inform you that, after long and deep study of the subject of partnership between your company and the foreign French company France Telecom/Agility, studying its different legal and realistic aspects, and in application of the authorities granted to our company by virtue of the terms of the meeting which was held on 21/4/2011 between our company and yours, and based upon the controlling role exercised by our company within the framework of verifying that the suspension conditions have been met, upon which the partnership was based to incur the appropriate legal results thereto, including the revocation of the mentioned partnership in light of the fact that the suspension conditions have not been collectively met, the Council of Trustees decided, in its session held on 24/6/2014, in report No. 19/2014, to consider the approval of our company based upon the principle of partnership dated 29/5/2011 as void and null as the suspension conditions, for which you were committed to fully carry out, have not been met by virtue of the report of the meeting dated 21/4/2011 and by virtue of your repetitive letters.

Thus, we inform you by virtue of this letter the final decision of our company by considering the partnership, desired between you and the foreign French company France Telecom/Agility, as void, null and invalid as the related suspension conditions have not been met, and for lack of evidence thereto without any legal or material effects of any part whatsoever. And we warn you in this respect to immediately proceed, within a period of no later than 15 days from the date of this letter, to reinstate the status as it was on 13/3/2011, take the procedures to revoke and terminate any contracts assigning shares in your company’s capital that were concluded after 13/3/2011, prove this revocation in the legal entries with the companies registrar and provide our company with a new statement proving return of shares to their main owners. Otherwise, your company shall bear all the legal consequences and necessary procedures will be taken against your company to compel you to obey and execute the content of the decision mentioned above.” 16

30. This document, referred to by the parties as the “CMC Decision”, was signed by Dr Rabee.

31. An appeal was filed with the CMC Appeals Board on 17 July 2014. On 18 August 2014, that Board affirmed the CMC Decision and rejected the appeal. On 16 October 2014, Korek filed a claim in the Iraqi High Administrative Court challenging the CMC Decision.17

32. On 12 November 2014, the CMC wrote again to Korek reminding it of the decision to invalidate the partnership with Orange and Agility and requiring it to submit evidence within 15 days proving that “the shares have been returned to their original owners”.18

33. 14 June 2015 was the due date for repayment of the principal of the IT Shareholder Loan. Neither Korek nor IH had paid back that principal by the due date nor any of the interest accrued under that loan and the IH Shareholder Loan from 2 September 2014.19

34. IBL issued a Notice of Default under the IBL Loan on 9 July 2015 and called on Korek and IH to refrain from making any payments under the IT Shareholder Loan, the IH Shareholder Loan or the Korek Guarantee. No repayment was made. IBL took no further action until 30 August 2017 when it sent a letter to Korek demanding payment and requesting that Korek provide additional security. In the event, IT investigated with IBL what collateral had been provided for the IBL Loan. IT then commenced arbitration proceedings against IBL in which IBL admitted that it had requested that the loan be secured with collateral and that such collateral had been provided in the form of cash. Discovery proceedings yielded bank records showing that on the eve of the execution of the IBL Loan, Mr Mustafa had transferred USD 150 million from an account held by him in HSBC in Dubai to an account with IBL in Beirut.20

35. On 25 January 2016, the Iraqi High Administrative Court dismissed Korek’s challenge to the CMC Decision for want of jurisdiction. Korek filed an appeal to the Iraqi Supreme Administrative Court on 21 February 2016. That Court convened on 18 January 2018 and rejected Korek’s challenge on that day.21

36. On 4 June 2018, IT commenced what was designated as “The First Shareholder Arbitration”. On 16 March 2020, IH made a request for arbitration leading to the arbitral proceedings the subject of this Appeal. After an unsuccessful attempt to consolidate that arbitration with its First Shareholder Arbitration, IT agreed to terminate the First Shareholder Arbitration without prejudice on 9 July 2020.

37. The Arbitration hearing, the subject of this Appeal, was conducted between 8 and 14 May 2022 and oral closing arguments made on 1 and 2 August 2022. The Final Award was issued on 20 March 2023.

The claims relating to the CMC Decision

38. There were a number of claims raised in the Arbitration. Relevant to this Appeal were claims relating to the CMC Decision. These included allegations of unlawful means conspiracy and breach of contractual and statutory obligations on the part of the Appellants.

39. By the unlawful means conspiracy claim, the Respondent IT, alleged that there was a corrupt scheme to procure the CMC Decision requiring IH and IT to exit from Korek and preventing the valid or effective exercise of the IT Call Option. Mr Mustafa and his associates were said to have procured the CMC Decision through cash payments, gifts, bribes and real estate transactions for the benefit of high-ranking CMC officials. These activities were said to have been carried out for the ultimate benefit of Mr Mustafa with the complicity of the Appellants who knowingly concealed the fraud and corruption from the Respondents. Their activities were said to have led to the letter from CMC of 10 December 2013 and the CMC Decision of 2 July 2014 declaring its approval of the 2011 transaction “void, null and invalid”. Those events were said to have given rise to two claims based in the tort of unlawful means conspiracy:

“(a) a derivative claim, brought on behalf of IH Ltd., against Mr Mustafa and CS Ltd for the destruction of the value of its shareholding in Korek; and

(b) a direct claim by IT Ltd against each of the Respondents for the destruction in value of the Call Option.” 22

40. IT further asserted that the procurement by the Appellants of the CMC Decision through bribery and corruption put them in breach of their contractual obligations under the SHA and the Subscription Agreement. They were also alleged to have breached statutory duties under Articles 120 and 124 of the Iraq Companies Law, Article 53 of the DIFC Companies Law 2009 and Article 1 of the DIFC Law of Obligations 2005. Further, KI was said to have been in breach of provisions of the SHA by allowing its appointed directors to the IH Board and the KSC to engage in bribery and corruption and, in breach of the Subscription Agreement, by failing to ensure that Mr Mustafa complied with all obligations under those Agreements. He was also said to have been in breach of the SHA by allowing Korek’s accounts to be used to make corrupt payments to CMC officials.23

41. Korek was also said to have been in breach of various provisions of the SHA and the Subscription Agreement in facilitating the bribery and corruption of CMC officials and in failing properly to contest the CMC Decision.

Invocation of the act of state doctrine in the Arbitration

42. The Appellants asserted in the Arbitration that the Tribunal had no jurisdiction to hear the claim that the CMC Decision was improperly procured through bribery and corruption because it would require the Tribunal to find that the CMC had been complicit in and issued the CMC Decision as a result of bribery and corruption. That, it was said, would require the Arbitral Tribunal to question the lawfulness of the CMC Decision and would offend against the foreign act of state doctrine. The Appellants contended in the Tribunal that the doctrine was applicable in the case before the Tribunal.24

43. In its Statement of Claim, IT rejected the argument submitting that the Appellants had not demonstrated that the foreign act of state doctrine should be applied by a DIFC-seated tribunal and had not cited any DIFC authority relating to the doctrine.

44. Further, IT said the doctrine was not engaged by its claims. It relied upon Belhaj v Straw [2017] AC 964 (“Belhaj”) in which the Supreme Court of the UK identified and discussed three rules within the foreign act of state doctrine. Its claims did not fall within the scope of any of those rules. They did not go to the validity or effect of foreign legislation and foreign governmental acts in respect of property within the State in question. Nor were they matters that were non-justiciable. None of its causes of action required the Tribunal to rule upon the validity or legal effectiveness of the CMC Decision.

45. IT also argued that it would be contrary to public policy, as well as to international public policy, to shield the acts in question from adjudication. 25

46. In response, the Appellants contended that the public policy exception was concerned only with the question whether the thing being done by the foreign state was, in its nature, so egregious that English law could not be seen to be deferential to that foreign state in breach of a peremptory norm. They made reference to Kuwait Airways Corporation v Iraq Airways Co. [2002] UKHL 19; [2002] 2 AC 883. The authorities showed that the focus would be on the act and its effect not on antecedent circumstances of the act or whether it could be impugned as a matter of irrelevant local law. 26

47. In its Reply in the Arbitral Proceedings, the Respondent IT rejected the argument that the foreign act of state doctrine was imported into DIFC Law. The absence of any recognition of the doctrine by the DIFC Court showed that the Tribunal should be slow to recognise that DIFC Law would automatically subscribe to the policy-driven considerations underpinning the English law development of the doctrine.

The Tribunal findings on the act of state defence

48. The Tribunal said it had not been provided with sufficient material on which it could make a finding that the foreign act of state doctrine would be applied in the courts of the DIFC as it had been applied in the English courts. The same applied to questions of public policy. That alone was said to be sufficient to dismiss the Appellants’ objection.27 Despite that, the Tribunal heard full argument on the applicability of the doctrine under English law.28 As the matter was said to go to jurisdiction it was no doubt prudent for the Tribunal to follow the course that it did.

49. The Tribunal held that the foreign act of state doctrine, whether or not recognised by the DIFC Courts in the same manner as in the English Courts, had no application to IT’s claims. IT was not challenging the legality or validity of the CMC Decision or that of the CMC Appeals Board. The claim had been advanced on the basis that the CMC’s Decision stood. It was as a result of the Appellants’ conduct that IT had suffered the loss of the value of its shareholding in Korek. The loss which IT had sustained was the result of the Appellants’ collusive conduct and their procurement of the CMC Decision.29

50. The Tribunal held that the act of state doctrine would not prevent inquiry as to the involvement of the Appellants in procuring a decree from the CMC in breach of the Appellants’ contract or as part of an unlawful act of conspiracy by the Appellants. The subject of the inquiry was the conduct of the Appellants and not the validity of the CMC’s decree under Iraqi law.

51. The Tribunal analysed the issues it had to determine to resolve the conspiracy, contractual and statutory claims connected with the CMC Decision.

52. In relation to the conspiracy claim, the relevant issues were said to be:

“(i) Whether the [Appellants] conspired amongst themselves to procure the CMC Decision and related actions;

(ii) Whether the [Appellants] had the requisite intention to injure IT Ltd and IH Ltd;

(iii) Whether the [Appellants] acted on this conspiracy by unlawful means; and

(iv) Whether, as a result, [the Respondents] suffered loss.” 30

53. As to the contractual and statutory claims, the Tribunal was to determine:

“(i) Whether the [Appellants] engaged in conduct to procure the CMC Decision to further their own private interests;

(ii) Whether the [Appellants] engaged in bribery and corruption;

(iii) Whether these actions breached the [Appellants’] contractual and statutory duties; and

(iv) Whether, as a result [the Respondents] suffered loss”.31

54. The Tribunal further held that even if the Respondents’ claims required findings of the invalidity or illegality of a governmental act, it was not satisfied that the doctrine of act of state could be invoked under DIFC Law to prevent examination of questions of bribery. Bribery of officials was a very serious matter and contrary to the statutory provision and public policy of countries right around the world.32

55. In dealing with the merits of the unlawful means conspiracy claim arising out of the CMC Decision, the Tribunal observed that there was no dispute between the parties that it should apply principles of English common law to the determination of the claim.33 The Respondents had pleaded that English law governed “all matters relating to the interpretation and application of the SHA, the Subscription Agreement, and the IraqCell Agreement. English law likewise governed any non-contractual obligations arising out of or in connection with the SHA, the Subscription Agreement, and the IraqCell Agreement, including obligations in tort.”34

56. The Appellants did not take issue with that assertion. They relied upon the English common law act of state doctrine on the basis that, absent any other provision, the default position was that the laws of England applied in the DIFC.

The Tribunal’s findings on unlawful conspiracy

57. On the basis of the evidence before it and the submissions of the parties, the Tribunal found on the balance of probabilities that there was an unlawful means conspiracy under which Mr Mustafa and his associates procured the CMC Decision with a view to using that Decision to force the Respondents out of Korek, to interfere with IT’s Call Option rights and so cause harm to the Respondents. This conspiracy was said to have been in place at the latest in December 2013 and was advanced through cash payments and real estate transactions for the benefit of high-ranking CMC officials. The activities were said to have been carried out with the complicity of the Appellants who knowingly concealed the fraud and corruption from the Respondents. The Tribunal acknowledged that the findings of fact were of a very serious nature. Nevertheless, the evidence when taken together overwhelmingly pointed to that conclusion. The Tribunal also made it clear that it reached that conclusion without reference to or reliance in any way upon anonymous hearsay statements made by the Respondents’ investigator, Mr Nicholas Bortman.35 The Tribunal went on to say:

“In reaching this decision, the Arbitral Tribunal has had regard to a number of factors. The effect of the evidence was cumulative such that taken together it had even greater force. Having said that some parts of the evidence were sufficiently striking by themselves as to point forcefully in one direction and one direction only. The absence of Mr. Mustafa at the hearing itself to answer questions and give oral evidence or indeed any witness from the [Appellants] was of further significance. The [Appellants] throughout their submissions tried to suggest that none of this evidence permitted any adverse conclusion regarding the CMC Decision or its procurement. The Arbitral Tribunal states clearly that it does not agree. Singly and collectively the evidence was both striking and damning.”36

58. There followed a detailed analysis by the Tribunal of the evidence going to the merits of the conspiracy claim. As the merits of its findings of fact are not in issue before this Court it is not necessary to canvass them in any detail.

59. The conclusion reached by the Tribunal was in the following terms:

“The Arbitral Tribunal therefore finds that:

(a) There was an agreement between, inter alios, (sic) Mr. Mustafa, CS Ltd, and Korek to procure the CMC Decision and the related actions of the CMC (including the amendment of the National License by way of the 3G Annex);

(b) The conspiracy had been formed and acted upon by the latest in December 2013;

(c) Each of the [Appellants] intended to injure IH Ltd, and IT Ltd;

(d) The acts performed to carry out the conspiracy were unlawful; and

(e) In consequence, IH Ltd, and IT Ltd each suffered a separate and distinct loss, as set out in Chapter R.”37

Allegedly hearsay and illegally obtained evidence referred to by the Tribunal

60. In its treatment of the unlawful means conspiracy claim, the Tribunal referred to the Appellants’ Rejoinder in relation to the evidence of Mr Bortman, who was the principal of Raedas Consulting Ltd (“Raedas”), a company based in London and specialising in investigations. Mr Bortman and his colleagues had interviewed a number of individuals said to be employed or to have been employed at Korek and at the CMC. None had produced a witness statement and none had appeared to testify before the Tribunal. Their evidence was given indirectly by way of witness statements from Mr Bortman. None of the sources was identified by name and their identities had been protected pursuant to a confidentiality regime.38

61. The Appellants argued that Mr Bortman’s evidence was central to IT’s case. Various propositions advanced by IT were said to “rest entirely” on Mr Bortman’s evidence.39 Mr Bortman’s evidence and the product of the Raedas evidence were said to be inadmissible. To the extent that they were admissible, the manner in which they had been gathered, collected and reported, meant that very little, if any, weight could be given to them. 40

62. The grounds of inadmissibility advanced by the Appellants before the Tribunal and referred to in the Final Award were in summary:

(i) Raedas engaged in widespread and pervasive unlawful and criminal conduct in obtaining the evidence on which IT sought to rely.

(ii) Mr Bortman’s witness testimony was a tendentious reportage of things said to have been told to his employees by unknown interlocutors.

(iii) The Appellants were prohibited, under a restricted access regime, from being told what documents procured by Raedas by its sources were and what they contained. The Appellants could not address the authenticity of those documents, their context and the circumstances in which they were created.41

63. The Appellants also submitted that no weight could be given to the allegations given that none of the sources had provided witness evidence in support of them. IT’s refusal to disclose their identity had prevented the Appellants from making any submissions regarding their credibility and reliability. The Appellants also contended that Raedas had made large cash payments and other inducements to its sources in return for information, which would have had an impact on the reliability and credibility of their allegations.42

64. The Appellants also argued before the Tribunal that no weight could be given to Mr Bortman’s own evidence purporting to summarise information given to him and his team by the sources that they interviewed.43

65. In a section of its Award dealing with the evidence of Mr Bortman and Raedas, the Tribunal acknowledged that very significant criticisms had been levelled by the Appellants at every stage of the proceedings against that evidence and against the testimony before the Tribunal and in other proceedings. The points taken before the Tribunal by the Appellants in relation to the evidence were summarised as follows:

(a) Raedas gathered evidence unlawfully by systematically making payments to public officials and Korek employees in return for confidential information obtained in the course of their employment and thereby committed offences in the UAE, in Iraq and in Turkey.

(b) Mr Bortman relied upon anonymised hearsay (and multiple hearsay) evidence. The DIFC Arbitration Law, UAE public policy, the IBA Rules and the principles of common law do not permit the use of anonymised evidence.

(c) The payment of witnesses undermined the weight that could be given to the evidence obtained.

(d) The investigative reports and memoranda produced by Raedas were not supported by the interview transcripts and ignored information relating to counterveiling case theories.

(e) The restricted access regime was falsely based on concerns for the safety of sources; and

(f) IT defied its obligation to produce the full universe of Raedas documents and shielded Mr Bortman through a persistent refusal to provide proper disclosure including “all contextual documents obtained by Raedas through its unnamed subcontracted investigators.44

66. Clarification was sought and provided on Days 1 and 3 of the evidentiary hearing as to the purpose for which IT sought to adduce Mr Bortman’s evidence.45 The Tribunal found that the sole statement upon which IT placed specific reliance was contained in paragraph 108 of Mr Bortman’s first witness statement concerning the interest of a Mr Rahmeh in an entity called Ersal. Mr Bortman had said that “witnesses, including former Korek employees, have identified Ms Haddad as a nominee shareholder for Mr Rahmeh”.46 The Arbitral Tribunal said it placed no weight on that statement and was not persuaded, in any event, that Ersal was used as a conduit for bribing members of the CMC.47

67. The Tribunal went on to say:

“More generally the Arbitral Tribunal recognises the concerns expressed by the [Appellants] regarding the hearsay nature of the statements attributed to Mr Bortman’s sources. It also has concerns about the statements that are attributed to the source identified as KE1. It appears to the Arbitral Tribunal that the evidence as summarised by Mr Bortman is not borne out by the transcripts of Ms Burton’s meetings and calls with that source.”48

In reaching its conclusions and making findings of fact, the Tribunal had placed no reliance whatsoever on any of the statements made by Mr Bortman’s sources. It had reached its conclusions on the basis of the documentary record, the testimony of the Orange and Agility witnesses and on other relevant matters which it had identified, such as Mr Mustafa’s failure to attend to give evidence, his behaviour in relation to the Arbitral Tribunal’s order, that he failed to provide evidence of sums deposited with IBL, and the Appellants’ failures in document disclosure. It mattered not whether the Raedas witness evidence was anonymised, hearsay, was paid for or was obtained in breach of some local legal requirement.49

68. The Tribunal also referred to arguments by the Appellants that it should afford no weight to a number of documents which had been obtained by Raedas. These were said to have been obtained by Mr Bortman from a subcontractor and that IT chose to withhold information or document production in respect of those documents with the result that the Arbitral Tribunal did not have any evidence on the record regarding their origin, context or veracity.50

69. The Tribunal said the fact that Mr Bortman obtained those particular documents or any other documents through a subcontractor was quite separate from the issues affecting the hearsay evidence of his sources. The Appellants had failed to challenge the authenticity of those documents within the time required by the Tribunal’s Procedural Order No 1 and did not do so before the Tribunal at that time. The obvious inference was that there was no basis for any challenge to be made. The Tribunal referred to conclusions which it had reached on the face of the documents without reliance on Mr Bortman’s assessment of their authenticity or otherwise.51

70. The Tribunal also rejected the Appellants’ submissions in closing that without the statements of Mr Bortman or his sources, IT’s case was irredeemably weakened. The Tribunal repeated its position in dealing with a list of matters set out by the Appellants and said:

“Insofar as that list contains hearsay statements from Mr Bortman’s sources, the Arbitral Tribunal has made clear above that it places no reliance upon those statements. It does not follow, however, that IT Ltd cannot rely upon Mr Bortman’s evidence that the Rabee family lived at the Higher Drive property – a statement supported by documentary evidence.”52

71. The Tribunal considered and found that without reliance upon or reference to the hearsay statements of Mr Bortman’s sources, the evidence firmly established on the balance of probabilities that the Appellants bribed the CMC through the purchase of properties in London in order to procure the CMC Decision and that they paid bribes to the CMC disguised as legal and consulting fees in order to procure the CMC Decision.53

72. In reaching that conclusion the Tribunal relied upon the observation of Romer LJ in Hovenden & Sons v Millhoff [1900] All ER Rep 848:

“If a bribe be once established to the court’s satisfaction, then certain rules apply. Among them the following are now established and, in my opinion, rightly established, in the interests of morality with the view of discouraging the practice of bribery. First, the court will not inquire into the donor’s motive in giving the bribe, nor allow evidence to be gone into as to the motive. Secondly, the court will presume in favour of the principal and as against the briber and the agent bribed, that the agent was influenced by the bribe; and this presumption is irrebuttable.”54

73. The Tribunal said that, in any event, it was satisfied that the evidence justified the inference that the CMC would not have issued the CMC Decision had the Appellants not bribed it.55

74. The Tribunal made specific reference to the letter of 22 January 2014 from Korek to the CMC. The Tribunal said:

“In fact it appears that the CMC received this letter on 26 January 2014, well after the deadline set by the CMC had passed. A copy of this letter was produced by Mr Bortman which appeared to have Dr Rabee’s handwriting and signature on it suggesting that an appointment should be scheduled with “senior management of the company”.56

75. Further on in the Final Award the Tribunal quoted submissions for the Respondents that there was overwhelming evidence that the CMC Decision was simply a pretext. It appeared to accept those submissions, one of which was that:

“The CMC hid Korek’s 22 January 2014 letter (a copy of which had Dr Rabee’s handwriting on it confirming receipt) and then later used the absence as a purported justification for the CMC Decision.57

In a footnote to this paragraph of the Final Award, the Tribunal said:

“This allegation is said by Mr. Hooker to be mere hearsay on the part of Mr. Bortman. What is clear, however, is that the letter from Korek does have manuscript writing on it which would appear to have been placed there by someone within the CMC, suggesting that the later statement that the letter had not been received was untrue. The Arbitral Tribunal does not understand the Respondents to have challenged the authenticity of either B2/1 or the marginal note, by whomever it was made.58

76. Later in the Final Award the Tribunal referred to arguments by the Appellants that it should afford no weight to a number of documents obtained by Raedas. These included an invoice referred to as the IC4LC Invoice of 25 April 2016, a Korek accounting spreadsheet and a ZR Group Aging Report. The Tribunal observed:

“The Respondents failed to challenge the authenticity of these documents within the time required by Procedural Order No. 1 and indeed do not do so now …”59

77. The same point is made by the Respondents in relation to the Korek letter of 22 January 2014.

The Application to Set Aside the Tribunal’s Award

78. On 20 June 2023, the Appellants filed a Claim seeking to set aside the Final Award pursuant to Article 41 of the Arbitration Law, DIFC Law No 1 of 2008 on bases set out in Particulars of Claim as follows:

“6. …

(a) pursuant to Articles 41(2)(a)(iii), 41(2)(b)(i) and 41(2)(b)(iii) of the Arbitration Law, that in failing to properly engage with and/or dismissing the [Appellants’] jurisdictional objections on the basis of the act of state principle and thereafter proceeding to consider evidence and rule on IT Ltd’s allegations in relation to the decision of the Iraqi Communications and Media Commission dated 2 July 2014 (the “CMC Decision”) the Tribunal exceeded its jurisdiction, rendered a decision on matters that are not arbitral and/or violated the public policy of the United Arab Emirates;

(b) further or in the alternative, pursuant to Article 41(2)(b)(iii) of the Arbitration Law, that in failing to rule upon the admissibility of hearsay evidence and maintaining the same on the evidential record the Tribunal created a serious doubt and perception that the same was relied upon implicitly and/or expressly or otherwise improperly impacted upon the consideration of the allegations made by IT Ltd;

(c) further or in the alternative, pursuant to Article 41(2)(b)(iii) of the Arbitration Law, that in relying, implicitly and/or expressly, upon evidence and documents procured through the investigation by Mr Nicholas Bortman and Raedas Consulting Ltd, the Tribunal:

(i) failed to deal with an issue in dispute between the parties; and

(ii) rendered an award that is in conflict with the public policy of the United Arab Emirates; and

(d) further or in the alternative pursuant to Article 41(2)(b)(iii) of the Arbitration Law, that the Tribunal relied upon a decision of a Tribunal constituted under the Rules of the Lebanese Arbitration and Mediation Centre, seated in Beirut, Lebanon, that has subsequently been set aside by the Beirut Civil Court of Appeal.”60

The reasons for the decision under appeal

79. In dismissing the Application to Set Aside the Award, which he did on 29 August 2024, the Primary Judge began by referring to the Tribunal’s conclusions that:

“(a) The Communications and Media Commission (CMC) Decision had been procured by corruption; unlawful means conspiracy, involving bribery and corruption of Iraqi state officials.

(b) A related award in an arbitration conducted under the Lebanese Arbitration and Mediation Centre (the LAMC Award) did not give rise to an issue estoppel in the Arbitration Proceedings.

(c) The Appellants did conspire by unlawful means to injure the Respondents in these proceedings.”61

80. On the first ground concerning the act of state doctrine which is central to this Appeal, His Excellency accepted that the doctrine is part of DIFC Law. He held that by the Appellants own admission the Tribunal had made no determination as to the validity of the CMC Decision, but instead had considered the acts of the Appellants in isolation in relation to the arbitrable matters at hand. The Tribunal’s findings did not affect or comment on the validity of the decision made within Iraqi jurisdiction. The Tribunal had kept its decision within the boundaries of its jurisdiction by making determinations on the Appellants’ acts leading up to the decision of the CMC.62 His Excellency held, for those reasons, that the Tribunal’s decision was lawful.

81. As to the public policy question, His Excellency held that, for there to be a violation of UAE public policy, a crime (within the context or procedure of the Arbitration) would have to have been committed on UAE soil. It was not enough to allege a misdemeanour to satisfy the public policy argument.63

82. A separate issue concerned the use by the Respondents of the evidence gathered by Mr Bortman and Raedas to show that the Appellants had colluded with former Iraq officials and CMC officials. It was contended that the methods used to gather that evidence rendered it inadmissible. The methods used included the gathering of intelligence from former Iraqi government officials, former and current Korek employees and former CMC officials.

83. The Tribunal had asserted that their determination was made without reference to or reliance on Mr Bortman’s anonymous hearsay evidence. However, the Appellants referred to extracts from the Final Award that quoted evidence drawn from Mr Bortman’s testimony and cross-examination. They argued that the Tribunal had consciously relied upon hearsay and double hearsay evidence in their determination.64

84. His Excellency said he did not find that the Tribunal had relied on Mr Bortman’s evidence to reach its conclusion. Its explicit statements excluded the evidence and even if the evidence had been relied upon, no breach of public policy could be found.65

85. The Tribunal was at liberty to use its discretion to determine the weight, if any, to be given to Mr Bortman’s evidence, which it decided was practically nil. In any event, the Respondents had shown through extracts from the Final Award, that the determination would have been the same irrespective of the weight given to that evidence. The threshold for setting aside the Award on procedural errors had not been met.66

86. His Excellency observed that hearsay evidence is permitted in the DIFC under the DIFC RDC. Irrespective of that fact, the rules of evidence did not engage UAE public policy. Public policy was engaged where criminal activity had occurred. No such activity had been shown to have occurred in the UAE.67

87. Evidence gathered by Raedas was not a “secret” pursuant to Article 432 of the UAE Criminal Code as CMC shareholders and third parties were involved in the sharing of the relevant information. There was no employee confidentiality obligation to breach. His Excellency reserved comment on whether there was criminal activity in Iraq. That was irrelevant to his determination as he was concerned with UAE public policy which would be engaged if criminal acts occurred in the UAE, which the Appellants failed to prove happened.68

88. His Excellency concluded that the Appellants had not proven that the Tribunal acted beyond its jurisdiction. It had not breached the act of state doctrine or UAE public policy when making the Award. The alternative submissions failed on a similar basis. No substantial proof was given to show that UAE public policy had been affected let alone breached by the Award or the subsequent enforcement of it in the DIFC.69

The grounds of appeal

89. The Appeal Notice in support of the Application for Permission to Appeal, was issued on 19 September 2024. The Skeleton Argument of that date filed on behalf of the Appellants, identified the following grounds of appeal:

“(1) The decision erred in its consideration and determination of the existence, scope and/or application of the doctrine of Foreign Act of State in the UAE;

(2) The decision erred in failing to engage properly or at all with considerations of public policy as they apply in the context of court or arbitral proceedings in or seated in the UAE with reference to evidence obtained illegally abroad and deployed in those proceedings.”

UAE international commitments on bribery of foreign officials

90. In 2006, the UAE ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (“UNCAC”) by Federal Decree No 8 of 2006. It also signed the Regional Arab Anti-corruption Convention made by the Arab League on 21 December 2010.

91. The Preamble to UNCAC included the following statement of concern by the State Parties:

“… that corruption is no longer a local matter but a transnational phenomenon that affects all societies and economies, making international cooperation to prevent and control it essential.”

92. Article 4 of the UNCAC is entitled ‘Protection of sovereignty’ and provides:

“1. States Parties shall carry out their obligations under this Convention in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of States and that of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States.

2. Nothing in this Convention shall entitle a State Party to undertake in the territory of another State the exercise of jurisdiction and performance of functions that are reserved exclusively for the authorities of that other State by its domestic law.”

93. The preceding provision must be read in conjunction with Article 16(1) which provides:

| “Article 16. | Bribery of foreign public officials and officials of public international organizations |

1. Each State Party shall adopt such legislative and other measures as may be necessary to establish as a criminal offence, when committed intentionally, the promise, offering or giving to a foreign public official or an official of a public international organization, directly or indirectly, of an undue advantage, for the official himself or herself or another person or entity, in order that the official act or refrain from acting in the exercise of his or her official duties, in order to obtain or retain business or other undue advantage in relation to the conduct of international business.”

94. Article 35 of the UNCAC provides:

| “Article 35 | Compensation for damage |

Each State Party shall take such measures as may be necessary, in accordance with principles of its domestic law, to ensure that entities or persons who have suffered damage as a result of an act of corruption have the right to initiate legal proceedings against those responsible for that damage in order to obtain compensation.”

95. The UNCAC entered into force on 14 December 2005.

96. The Regional Arab Anti-corruption Convention includes a Protection of Sovereignty provision, in Article 3, which mirrors that contained in the UNCAC. Article 4, according to its domestic legislation, shall adopt the necessary legal and other measures to criminalise listed acts when committed intentionally. These include:

“4 —Bribery of foreign public officials and officials of public international organizations in connection with international trade with a State Party.”

97. Against the background of the UAE’s international legal commitments it is apparent that at the time of the alleged bribery, its public policy stood firmly against the bribery of foreign officials. That has been reinforced by the new Penal Code, referred to below, which expressly criminalises bribery of foreign public officials or employees of international organisations.

98. It should also be noted that international conventions achieved the force of law in the UAE by ratification and become part of the applicable domestic laws of the State to be given effect to by UAE judges. In Pearl Petroleum Company Ltd v The Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq [2017] DIFC ARB 003, (20 August 2017) (“Pearl Petroleum”), Justice Sir Jeremy Cooke, citing Dubai Court of Cassation Case 87/2009 observed:

“By virtue of the terms of Article 5 of Federal Law No 8 of 2004 … although the civil and commercial laws of the UAE are not applicable in DIFC, the DIFC remains bound by the terms of the Treaties which form part of the law of the UAE.”

Statutory framework

UAE — Federal Law No. (8) of 2004 on Financial Free Zones

99. Article 5 of the above Law provides:

“Financial Free Zones must not perform any activity that results in the breach of an international treaty to which the State has adhered or will adhere.”

UAE — Penal Code

100. The Penal Code of the UAE, as it stood in 2013 — Federal Law No. 3 of 1987, when the alleged bribery took place, criminalised the bribery of domestic public officials. The Penal Code was replaced by Federal Law No. 31 of 2021 which was later amended by Federal Decree No. 36 of 2022. The Penal Code now criminalises bribery, inter alia, of foreign public officials or employees of international organisations.70

UAE Civil Code — Federal Law No. (5) of 1985

101. Chapter 1 of the UAE Civil Code contains provisions relating to the application and effect of the “Civil Transactions Law” of the UAE. Part 1 of Chapter 1 deals with the law and its application and in Article 1 sets out a default provision allowing a judge to render judgment in accordance with custom “but provided that the custom is not in conflict with public order or morals …”

102. The term “public order” appearing in Article 1 was defined non-exhaustively in Article 3 of the UAE Civil Code. This was invoked by an expert witness called by the Appellants in their Application to Set Aside the Final Award. The witness was Dr Habib Mohammad Sharif Al Mulla. The English translation, as appears from a UAE legislation site, is as follows:

“Article 3

Public order shall be deemed to include matters relating to personal status such as marriage, inheritance, and lineage, and matters relating to sovereignty, freedom of trade, the circulation of wealth, rules of private ownership and the other rules and foundations upon which society is based, in such a manner as not to conflict with the definitive provisions and fundamental principles of the Islamic Shari’a.”

103. The version offered by Dr Al Mulla in his statement read as follows:

“… Shall be considered of public policy, provisions relating to personal status such as marriage, inheritance, lineage, provisions relating to systems of governance, freedom of trade, circulation of wealth, private ownership and other such rules and foundations on which the society is based provided that these provisions are not inconsistent with the imperative provisions and fundamental principles of the Islamic Shari’a.” (emphasis added by Dr Habib)

104. According to Dr Al Mulla, Article 3 provides guidance on rules considered to be public policy provisions in the UAE. Given the non-exhaustive character of the list of matters falling into the category of “public order” in Article 3, it does not seem that it can be read as a provision which limits the concept of public policy in the UAE. In any event, it also picks up “other rules and foundations upon which society is based”.

Dubai Law — The Judicial Authority Law No 12 of 2004

105. The Judicial Authority Law No 12 of 2004, a law made by the Ruler of Dubai, provides for the jurisdiction of the CFI in Article 5A. The Court has exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine, inter alia, under Article 5A(1)(e):

“any claim or action over which the Courts have jurisdiction in accordance with DIFC Laws and DIFC Regulations.”

Article 6 provides for the governing law in the following terms:

“The Courts shall apply the Centre’s Laws and Regulations, except where parties to the dispute have explicitly agreed that another law shall govern such dispute, provided that such law does not conflict with the public policy and public morals.”

106. Article 7(4) makes provision for judgments, decisions and orders rendered by the Dubai courts or arbitral awards ratified by the Dubai courts to be executed by the Execution Judge of the Courts.

Dubai Law — DIFC Court Law No. 10 of 2004

107. The DIFC Court Law, a law made by the Ruler of Dubai, states its purpose in Article 6 thus:

“6. Purpose of the Law

The purpose of this Law is to provide for the independent administration of justice in the DIFC in accordance with Dubai Law No. 9 of 2004 and the Judicial Authority Law.”

108. The jurisdiction of the DIFC CFI relevant to this Appeal is set out in Article 19(1)(a):

“19. Jurisdiction

(1) The DIFC Court of First Instance has original jurisdiction pursuant to Article 5(A) of the Juidicial Authority Law to hear any of the following:

…

(a) any application over which the DIFC Court has jurisdiction in accordance with DIFC Laws and Regulations;”

109. Article 30 of the DIFC Court Law deals with the governing law of the DIFC Courts as follows:

“30. Governing Law

(1) In exercising its powers and functions, the DIFC Court shall apply:

(a) the Judicial Authority Law;

(b) DIFC Law or any legislation made under it;

(c) the Rules of Court; or

(d) such law as is agreed by the parties.

(2) The DIFC Court may, in determining a matter or proceeding, consider decisions made in other jurisdictions for the purpose of making its decision.”

Dubai Law — DIFC Court Law (No 2) of 2025

110. This is a Law recently made by the Ruler of Dubai. It postdated the decision under appeal. In Article 14A it sets out the jurisdiction of the DIFC Courts, which includes:

“5. Claims and applications for the ratification or recognition of Arbitral Awards, in accordance with the Arbitration Law in force within the DIFC.

6. Claims and applications arising from or related to any arbitration procedures where:

i. the seat or legal place of arbitration is the DIFC;

ii. arbitral proceedings take place within the DIFC, and the parties have not agreed on the seat or legal place of arbitration; or

iii. the parties agree to the DIFC Courts’ jurisdiction for disputes arising out of arbitration proceedings.”

Dubai Law — The Law on the Application of Civil and Commercial Laws in the DIFC — DIFC Law No. 3 of 2004

111. The Law on the Application of Civil and Commercial Laws in the DIFC, Law No. 3 of 2004 was the Law as it stood at the time of the Arbitration and the Final Award and at the time of the Application to Set Aside the Award. Relevant provisions of the Law are set out below.

“3. Application of the Law

This Law applies in the jurisdiction of the Dubai International Financial Centre.

....

7. The objectives of this Law

The objectives of this Law are to:

(a) provide certainty as to the rights, liabilities and obligations of persons in relation to civil and commercial matters arising in the DIFC; and

(b) allow persons to adopt the laws of another jurisdiction in relation to civil and commercial matters arising within the DIFC.”

112. Articles 8 and 9 of the Law provided:

“Application

(1) Since by virtue of Article 3 of Federal Law No. 8 of 2004, DIFC Law is able to apply in the DIFC notwithstanding any Federal Law on civil or commercial matters, the rights and liabilities between persons in any civil or commercial matter are to be determined according to the laws for the time being in force in the Jurisdiction chosen in accordance with paragraph (2).

(2) The relevant jurisdiction is to be the one first ascertained under the following paragraphs:

(a) so far as there is a regulatory content, the DIFC Law or any other law in force in the DIFC; failing which,

(b) the law of any Jurisdiction other than that of the DIFC expressly chosen by any DIFC Law; failing which,

(c) the laws of a Jurisdiction as agreed between all the relevant persons concerned in the matter; failing which,

(d) the laws of any Jurisdiction which appears to the Court or Arbitrator to be the one most closely related to the facts of and the persons concerned in the matter; failing which,

(e) the laws of England and Wales.

9. Submission to jurisdiction

(1) The Court shall determine any matter before it in accordance with the laws that may apply by virtue of Article 8.

(2) An Arbitrator shall determine any matter before him in accordance with the laws that may apply by virtue of Article 8.”

113. The term “Jurisdiction” is defined in Schedule 1 of the Law in the following terms:

“Jurisdiction any jurisdiction in any country for the time being recognised by the UAE.”

These provisions appeared in the DIFC Law No 3 of 2004 in a Consolidated Version dated March 2022 and reflect amendments by the DIFC Laws Amendment Law, DIFC Law No 2 of 2022.

114. In Pearl Petroleum Justice Sir Jeremy Cooke referred to Article 8 as incorporating “waterfall” or “cascade” provisions as it provides for a hierarchy for determining the applicable law.71 He described the jurisdiction as “founded on statutory provision which requires the law of the DIFC to be first applied and only in absentia to move on to the cascading subparagraphs’ provisions, of which the last is the law of England and Wales, …”72 As appears below, since the 2024 amendment to the Law the DIFC Courts have been empowered to determine the common law for the DIFC having regard to the common law of England and Wales and other common law jurisdictions.

Dubai Law — Law on the Application of Civil and Commercial Laws in the DIFC as amended by DIFC Law No. 8 of 2024

115. This Law post-dated the Arbitration, the Final Award and the decision under appeal. Article 8 of the Law as amended in November 2024 provides:

“8. Choice of applicable law

(1) Since by virtue of Article 3 of Federal Law No 8 of 2004, DIFC Law is able to apply in the DIFC notwithstanding any Federal Law on civil or commercial matters, the rights and liabilities between persons in any civil or commercial matter are to be determined according to the laws for the time being in force in the Jurisdiction chosen in accordance with paragraph (2).

(2) The relevant Jurisdiction is to be the one first ascertained under the following paragraphs:

(a) so far as there is a regulatory content, any applicable DIFC Statute; failing which,

(b) the law of any Jurisdiction other than that of the DIFC expressly chosen by any DIFC Statute; failing which,

(c) the laws of the Jurisdiction as agreed between all the relevant persons concerned in the matter; failing which,

(d) the laws of a Jurisdiction which appears to the DIFC Court or Arbitrator to be the one most closely related to the facts of and the persons concerned in the matter; failing which,

(e) DIFC Law.”

116. A new Article 8A. entitled “Content of DIFC law” provides as follows:

“8A. Content of DIFC Law

(1) The following provisions apply where DIFC Law is the law applicable to a civil or commercial matter pursuant to Article 8 above.

(2) The content of DIFC Law shall be determined by any applicable DIFC Statute, and any DIFC Court judgments interpreting and applying the applicable DIFC Statute in a manner consistent with this Law.

(3) The common law (including the principles and rules of equity) supplements DIFC Statute except to the extent modified by this Law or any other DIFC Law. The DIFC Courts in determining the common law for the DIFC in any case may have regard to the common law of England and Wales and other common law jurisdictions.

(4) The common law of the DIFC (including the principles and rules of equity) as determined by the DIFC Courts, must not be inconsistent with DIFC Statute.

8B. Interpretation of DIFC Statutes

(1) The interpretation of DIFC Statutes may be guided by:

(a) jurisprudence from common law jurisdictions regarding the interpretation and application of analogous laws; and

(b) the rules and principles of statutory interpretation from common law jurisdictions.

(2) Article 8 B(1) applies to all DIFC Statutes, regardless of whether the relevant DIFC Statute is based on an international model law or another non-common law source.

(3) If a DIFC Statute is based on an international model law, its interpretation may also be guided by international jurisprudence interpreting and applying the international model law, as well as interpretive aids and commentary published by international bodies regarding the international model law.”

DIFC Law — Arbitration Law — DIFC Law No 1 of 2008 as Amended by DIFC Amendment Law No 1 of 2013

117. The DIFC Arbitration Law applies in the jurisdiction of the DIFC (Article 3). The law applies where the seat of the arbitration is the DIFC (Article 7(1)). Article 10 provides:

“10. Extent of court intervention

In matters governed by this Law, no DIFC Court shall intervene except to the extent so provided in this Law.”

118. Article 12 of the Arbitration Law provides for the definition and form of arbitration agreements. Article 12(2) provides that certain classes of arbitration agreement cannot be enforced unless certain conditions are met. These are arbitration agreements relating to contracts of employment within the meaning of the Employment Law 2005 and contracts for the supply of goods or services to a consumer by a supplier who is a natural or legal person acting for purposes relating to his trade, business or profession whether publicly owned or privately owned.

119. The jurisdiction of arbitral tribunals is dealt with in Chapter 4, and the conduct of arbitral tribunals in chapter 5. Chapter 7 deals with recourse against awards. It comprises Article 41, relevant parts of which provide:

“41. Application for setting aside as exclusive recourse against arbitral award

(1) Recourse to a Court against an arbitral award made in the Seat of the DIFC may be made only by an application for setting aside in accordance with paragraphs (2) and (3) of this Article.

(2) Such application may only be made to the DIFC Court. An arbitral award may be set aside by the DIFC Court only if:

(a) the party making the application furnishes proof that:

....

(iii) the award deals with a dispute not contemplated by or not falling within the terms of the submission to Arbitration, or contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to Arbitration, provided that, if the decisions on matters submitted to arbitration can be separated from those not so submitted, only that part of the award which contains decisions on matters not submitted to Arbitration may be set aside; or

...

(b) the DIFC Court finds that:

(i) the subject-matter of the dispute is not capable of settlement by arbitration under DIFC Law;

(ii) the dispute is expressly referred to a different body or tribunal for resolution under this Law or any mandatory provision of DIFC Law; or

(iii) the award is in conflict with the public policy of the UAE.”.

Articles 41(3) and 41(4) are not material for present purposes.

120. Articles 42, 43 and 44 of the Law deal with recognition and enforcement of awards. Article 44 includes grounds for refusing recognition and enforcement which reflect the grounds for setting aside an award in Article 41.

Whether the Application Law amendment was retrospective

121. It is appropriate at this point to deal with a submission by the Appellants made in reliance upon the recent amendments to the Application Law. They relied upon Article 7(e) and the new Article 8A for the proposition that the DIFC Court can now develop its own common law by reference to the jurisprudence of common law jurisdictions other than England and Wales provided that the development is not inconsistent with the DIFC Statutes.

122. In a footnote to their written submissions, the Appellants acknowledged that the amendment was not in force at the time that the Tribunal delivered its Final Award and held that the Appellants had not demonstrated that the act of state doctrine should be applied by a DIFC-seated tribunal.73

123. The Respondents submitted that the amended Application Law and the development of DIFC Law based on it do not have retrospective effect. They cited Abdelsalam v Expresso Telecom Group [2021] DIFC CA-011 (20 December 2021) in which the Court of Appeal had said:

“The general rule of the common law is that a statute changing the law ought not, unless the intention appears with reasonable certainty, to be understood as applying to facts or events that have already occurred in such a way as to confer or impose or otherwise affect rights or liabilities which the law had defined by reference to past events.”74

This was subject to an exception for procedural laws regulating the manner in which rights and liabilities fixed by reference to past facts, matters or events were to be enforced. That approach was followed in a decision of this Court in TIG v EL Fadie Hamid [2022] DIFC CA-005/006 (20 September 2022) at paragraph 62.

124. The Court accepts the Respondents’ submissions.

125. To the extent that the Application Law was relevant in the Appeal, it was the Application Law as it stood prior to the amendment. However, as appears from the reasons below, even on the assumption that it was the amended Application Law that applied, the outcome would be the same.

Expert testimony

126. Two expert witnesses were called in the Set Aside Application on the question of UAE public policy so far as it relates to scrutiny by UAE courts and tribunals of the acts or omissions of foreign states. They gave their own statements and a Joint Report setting out points of agreement and disagreement. There was no expert testimony before the Tribunal on the act of state doctrine as an aspect of UAE public policy. That testimony was only brought in the Set Aside Application.

127. Although the testimony appears to have been treated as evidence in the Set Aside Application, there is a question whether it was. Consistently with the approach adopted by this Court in the past, it would be appropriate to treat expert testimony on UAE law as a species of submission. In Fidel v Felecia [2015] DIFC CA 002 (23 November 2015), the Court referred to expert testimony on a question of UAE public policy. It held that DIFC Courts could treat such testimony on UAE law as legal submissions consistent with the practice of international arbitration. Chief Justice Michael Hwang said:

“The presumptive rule should be that legal experts are to write briefs with their analysis of the relevant legal principles of the applicable or relevant law, and to make further submissions applying the legal principles to the facts as alleged by the respective parties, or to argue for a particular decision to be delivered by the Court.”75

128. The Chief Justice made clear that the above was only a presumptive rule and the trial judge should always have the discretion to proceed in the manner which was considered most beneficial to the judge’s education.

129. In that case, as in this, the Court was dealing with a question of UAE law. Indeed the “international approach” is applicable to questions of foreign law generally. In Nest Investments Holding Lebanon SAL v Deloitte & Touche (M.E.) [2021] DIFC CA 014 (8 December 2021), a case involving a question of Lebanese law, the Court held that the “international approach” enunciated by the former Chief Justice to be clearly appropriate.

130. The parties’ experts in this case gave testimony on two disparate issues. One was whether the public policy of the UAE accommodates the act of state doctrine. The other related to the question whether the gathering of evidence by the Respondents’ investigators involved unlawful acts such that use of the evidence would be contrary to UAE public policy.

131. The Primary Judge did not canvass the expert testimony on the first question at any length holding that:

“It is clear that the act of state doctrine exists in DIFC law simply on the concept that the DIFC, has its own jurisdiction, is still bound by the public policy of the UAE and of international legal matters as a part of the UAE.”76 .

It is nevertheless appropriate to review the expert testimony.

Expert Testimony — Dr Habib Mohammad Shariff Al Mulla

132. The expert witness called by the Appellants, Dr Habib Mohammad Shariff Al Mulla, opined that:

“… the public policy of the UAE precludes courts and tribunals based in the UAE from considering the acts or omissions of foreign states. Therefore, courts in the UAE or an arbitral tribunal seated in the UAE may not consider the acts or omissions of a foreign state, as any such consideration violates the laws and public policies of the UAE.”77

133. He cited Article 3 of Federal Law No (5) of 1985, the UAE Civil Code, albeit in a translation that differed in its wording from that provided on the UAE government legislative website. He rightly footnoted that citation with a reference to the undefinable and elusive character of public policy.

134. The application of the public policy of the UAE in the DIFC was said to be confirmed by Article 41(2)(b)(iii) of the Arbitration Law. In Loralia Group LLC v Landen Saudi Company [2018] DIFC ARB 04 (23 April 2020) (“Loralia Group”), His Excellency Justice Shamlan Al Sawalehi referred to Articles 41(2)(b)(iii) and 44(1)(b)(7) of the DIFC Arbitration Law and observed:

“It is important to note that the wording here is specific and refers to the public policy of the “UAE” (and is not a reference to the public policy of “Dubai” or the “DIFC”). This is because federal public policy applies throughout the UAE in a unitary and indivisible nature.”78

135. In relation to the act of state doctrine, Dr Al Mulla contended that “as a matter of principle courts in the UAE may not adjudicate on the acts of a foreign administrative or state agency”.79 In support of that proposition, he cited a judgment of the Federal Supreme Court in 714/2018 in which it was said:

“It is resolved in jurisprudence and administrative law, and as accustomed by judicial practice, that the conditions of a challenge against an administrative resolution include that it shall be issued by a national administrative authority. So, a resolution issued by a foreign administrative authority may not be argued with before the administrative judiciary of another country, which is a material condition that is consistent with the concept of the sovereignty of the State, whereby public entities or authorities in the country extract the competencies and authorities thereof from the sovereignty of the State as an expresser thereof. Such sovereignty does not take effect versus other states and the subsidiary authorities thereof in general. Therefore, a resolution issued by an administrative authority of another country may not be argued with, even if such authority is a regulatory authority between the members thereof, represented by other states, as long as the rules of the law in force in the territory governing the same is the law applicable and these rules are associated with the public order.” (emphasis added by Dr Al Mulla)

136. The reference to administrative courts did not mean that non-administrative courts could entertain such a claim. Dr Al Mulla formulated the principle he took from the decision of the Federal Supreme Court as follows:

“A decision issued by a foreign administrative body may not be litigated before any courts of the UAE or a UAE seated tribunal.”80

137. With respect the “principle” thus stated begs the question — what does it mean to litigate a decision issued by a foreign administrative body?

138. The act of state doctrine was said to constitute “an absolute rule relating to the public policy of the UAE”. There were “no exceptions that would allow a UAE court or tribunal seated in the UAE to examine the acts or omissions of a foreign state.”81

139. An allegation that the act of state in question was the result of corruption was said to have no bearing on the application of the public policy rule which prohibits the review of foreign acts of state in its entirety.82

140. As appears later in these reasons the formulation by the Federal Supreme Court in 714/218, as reflected in the translated reasons, conveys a rather narrow concept of a foreign state principle. Moreover, it does not appear to have been a case in which a foreign act of state was involved.

Expert Testimony — Mr Ali Al Hashimi

141. A different view was offered by Mr Ali Al Hashimi,83 a legal practitioner licensed to practice throughout the UAE who has 23 years of experience as a litigation practitioner in that jurisdiction. He has previously been called on as an expert witness on UAE Law in arbitration proceedings and before DIFC and foreign courts.

142. He observed that Article 3 of the Civil Code of the UAE does not provide an exhaustive list of matters covered by public policy. There is no express reference to the act of state doctrine in UAE legislation. The closest concept is that of the sovereign acts of a foreign state. The scarcity of judgments on the doctrine suggested that its scope and potential exceptions remain to be articulated by the local courts.

143. Mr Al Hashimi considered that the decision of the Federal Supreme Court 714/2018, invoked by Dr Al Mulla, precluded hearing a challenge to or appeal from the administrative decision of a foreign state — a preclusion based on the principle of state sovereignty. An award which did not directly challenge the legality of the acts of a foreign government that had taken place within the territory of the foreign state, would not be considered to have infringed the act of state doctrine to the extent it existed under UAE law.